Part 2: Jacket Characteristics

Jump to:

Introduction to Part 2

Part 2 of this presentation will explore the characteristic details in pattern and construction that define the “Richmond Depot” jacket. To illustrate the characteristics described, photographs of original examples from the study will be used. In some instances, variations or “anomalies” will be illustrated through comparison of the same aspect of several jackets. At the end of Part 2, some commonly held beliefs (myths) about these jackets will be discussed based upon the fifteen studied jackets to access their validity. Finally, some summary conclusions on the typical characteristics of RD jackets will be presented.

The "Richmond Depot Type II," as defined by Les Jensen

Richmond Depot type II Jackets – “Jensen Characteristics”:

Six piece body pattern with two piece sleeves

Stand up collar

9 button front (almost always)

Epaulettes (non functional)

Belt loops

Top stitched edges

Heavy cotton lining

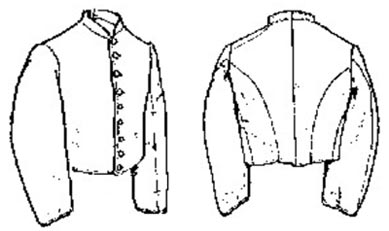

In his 1989 article Les Jensen outlined characteristics associated with jackets produced by the Richmond Clothing Bureau based upon his study of both photographs and existent examples, many of which are included in this study. The jacket design is based upon a relatively common 19th Century men’s garment pattern used in both civilian and military coats. The six-piece body pattern with flared two-piece sleeves, stand-up collar and features such as epaulettes and belt-loops are like the pattern of Federal uniforms (e.g. mounted service jacket) and state issued short jackets used by both Confederate and Union troops. Most frock coats utilized elements of the pattern as well.

RD II Jacket Characteristics – Front

The Fifth Maine Museum example from the study illustrates the major elements of the RD type II jacket characteristics as discussed by Jensen. While not specifically referenced by Jensen in his discussion of this type of jacket, the top stitching at the cuff is also regularly found on RD jackets. In subsequent slides will further examine some of these characteristics.

All the type II jackets examined in the study conform to the characteristics outlined by Jensen. These four exhibit slight variations encountered among them as well, some the result of anomalies in manufacture and some due to post manufacture, in-service modifications. The Haines jacket as was pointed out earlier in Part 1 is a well-executed example of the conversion of a simple enlisted man’s jacket into a uniform jacket or possibly fatigue jacket for an officer’s use. To facilitate the conversion (or improve the appearance) the epaulettes and belt loops were removed at the time insignia and trim was added probably by a seamstress or tailor to Haines specifications. Epaulette removal seems to have been a major post issue modification by enlisted soldiers in the field as seen in the Greer and NPS examples. The Greer jacket is also at variance with the other RD type II jackets in the study because of the six-button format down the front rather than the usual nine. While the Brunson jacket from the front exemplifies the “Jensen Characteristics”, its construction almost entirely by sewing machine is an unusual and significant variation from the “norm”.

John J Haines jacket – epaulettes & belt loops removed – 2nd Lt. insignia and trim added

Gettysburg NPS jacket – epaulettes removed

George HT Greer jacket – six button front & epaulettes removed

J W Brunson jacket – nearly all machine sewn

RD II Jacket Characteristics – Back

Looking at the back of RD jackets, other elements of the pattern are visible on the Fifth Maine Museum example. The cut of the jacket across the shoulders and at the waist is exemplary of the design concept for a fitted men’s coat in the mid-19th century. As practical clothing for field fatigue use these jackets were executed in a reasonably stylish manner. The belt loops seen on each side at the seam between the side panels and the front were sometimes removed by soldiers in field modifications.

The four jackets shown further illustrate the elements of pattern implementation.

John J Haines jacket – belt loops removed

Gettysburg NPS jacket

George H T Greer jacket

John Blair Royall jacket

RD II Jacket Characteristics – Collar

This closeup of the collar and neck on the Fifth Maine Museum example illustrates this area in “typical” RD type II jackets in the study. The collars for type IIs measured approximately 1 ½ inches in height at the highest point in front and at the center back on all the originals examined. The gently rounded front was seen in seven of the eight type IIs in the study. The lone exception to this was the Ramsey Jacket which will be discussed in more detail later. All type IIs (and type IIIs for that matter) have top stitching around the edge of the collar. Also, typical of all the type II jackets was the presence of a line of top stitching on the collar above the neck seam. The purpose for this most likely was to tie together the two sides of the collar and, where interlining was used to stiffen the collar, prevent it from moving or becoming displaced.

The four RD type II examples pictured here show the characteristics discussed on the last slide. On the Bryan jacket, the visible top stitching is executed in machine stitching as it is elsewhere in that specific example. The Greer and Gettysburg NPS are hand top stitched in neatly done “running” stitches while the Royall example is "back" stitched.

John Blair Royall jacket

Gettysburg NPS jacket

George Pettigrew Bryan jacket

George H T Geer jacket

RD II Jacket Characteristics – Epaulettes

The epaulette design and implementation in the Fifth Maine Museum jacket is typical of what was seen on six of the eight RD type IIs in the study. Those were constructed of two separate pieces of fabric, sewn around the two long edges and rounded tip, turned inside out, and then top stitched along the edge. Once completed, they were “sandwiched” between the coat body and the sleeve at the top of the shoulder when the sleeve was attached. The epaulettes were cut off the Haines and Greer jackets and only remnants are still visible. The Ramsey jacket is again a divergent example in the way it is constructed. Researcher Dan Wambaugh indicates that on the NPS example, the stitching at the armscyes (arm holes) was opened to remove the epaulettes and then neatly closed so that their original configuration is indeterminate. On all jackets in the study where epaulettes are found they are non-functional, i.e. the button is sewn through the epaulette and coat body rather than using buttons with buttonholes for fastening them. In other words, they were purely decorative and equipment straps (e.g. the one for the cartridge box) could not be easily secured under the epaulettes perhaps explaining the practical reason many were cut off in the field.

Three additional examples of type II epaulettes seen on jackets from the study. The red (Artillery) “branch of service” piping on the John Blair Royall jacket is clearly visible. The addition of “branch of service” trim by the RCB at the time of production is unique among surviving Richmond Depot jackets. The cording on the epaulette of the Bryan example was probably done post issue when it was personalized for Bryan’s use as an officer’s jacket. Because he was killed in August 1864, it is unlikely that it was a post-war addition like the trim on the Henry Redwood example. The lone surviving Gibson Contract wooden button on the Brunson jacket, seen in this view, is virtually identical to those on the Fifth Maine Museum example.

John Blair Royall jacket

George P Bryan jacket

Joseph W Brunson jacket

Somewhat frequently soldiers in the field modified their jackets by removing the epaulettes which, as has been noted earlier, were nonfunctional. These pictures show two examples from the study where they have been removed simply by cutting them off.

John J Haines jacket

George HT Greer jacket

RD II Jacket Characteristics – Belt Loops

The belt loops installed on RD type II jackets in the study basically were all close in size (ranging from 3/4” – 7/8” wide, 3 ¼” – 3 ½” long). Belt loops were also sometimes removed by soldiers in the field. Unlike belt loops found on many contemporaneous Federal and Confederate examples, they did not have buttons but were directly applied to the body of the jacket, usually sewed through all layers. In one example, the Brunson jacket, they were attached only to the outer body before the lining was attached. While only a minor variation (“seamstress choice”), two locations seemed to be used, either aligned in front of the side seam or centered on it.

Shown are four additional examples of belt loops on jackets in the study.

John Blair Royall jacket – centered on side seam

Gettysburg NPS jacket – slightly forward of side seam

George H T Greer jacket – centered on side seam

Joseph W Brunson jacket – forward of seam and sewed through outer shell before lining added

The Ramsey jacket, as pointed out above, exhibits subtle differences from the other type II examples in the study. The reasons for these are not known. The jacket apparently never had belt loops. The epaulette design is slightly different being “pointed” instead of “rounded” at the end. Its construction has also changed to only a single piece of material with the edges turned under and sewed down. These changes would save on both material and construction time. However, they could also be explained by “seamstress choice,” possibly adaptation to random deficiencies in the number of pieces supplied in the “kit” as received (i.e. two instead of four epaulette pieces and missing belt loops).

George William Ramsey jacket – collar and epaulettes (no belt loops) (transition characteristics?)

Perhaps the most significant design variance in the Ramsey jacket is the collar profile which has a more “angular” shape as opposed to the gently rounded style seen on the other RD type II examples in the comparison group. The appearance of this collar style in most of the RD type III jackets studied supports speculation that this example represents a transition piece or, at the very least, was produced very late in type II production. Its provenance does not provide specific clues to its dating but its condition and the fact that it was likely the jacket Ramsey was wearing upon his capture suggests it is a late RD type II. Unfortunately, as pointed out earlier, since it is on display in the “Price of Freedom” exhibition at the Smithsonian, further examination or photography is prevented at this time.

RD III Jacket Characteristics

It appears in mid-1864, the RCB made minor changes to the standard jackets it produced. The basic jacket pattern remained the same but the epaulettes and belt loops, features often removed by the soldiers in the field, were dropped. While the “standard” remained 9 buttons on the front of the jacket, 8 button fronts appear occasionally. Finally, all examples studied are constructed of heavy, “kersey” twill EAC implying that Confederate purchasing agents in England had standardized their procurement on such fabric. It is impossible to state with any degree of certainty if only EAC was used for type IIIs but the prodigious amounts run through the Blockade in the second half of 1864 does suggest it was heavily employed in RCB uniform production (source: The Shipping Book – Richmond Depot, 1863 – 1865, RG 109 NARA).

The "Richmond Depot Type II," as defined by Les Jensen

Richmond Depot type III Jackets – “Jensen Characteristics”:

Basic Pattern remained the same as RD type II

9 button front continued (for the most part)

“Simplified” by deleting both epaulettes and belt loops

RD III Jacket Characteristics – Collar

Circumstantial evidence from five RD type III jackets in the study (as well as several others in the extended group) suggests modification of the collar profile may have occurred between the end of RD type II and start of RD type III production. The change to a more “angular” design is discussed relative to the late type II Ramsey jacket. However, yet another collar profile is also seen on some type III examples further complicating definite conclusions.

A feature believed unique to type IIIs is the inclusion of “darts” in the neck on the Wilson and Pilcher jackets. These may have been modifications made after production but careful examination of the neck region on both jackets showed no definite evidence of such activity. It seems doubtful they represent “seamstress choice” variations due to the extra work involved in implementing them if not part of the original pattern. They could represent “experimental” changes made by the RBC to achieve better fit, which were subsequently dropped (the Federal Schuylkill Arsenal may have done similar things based upon surviving examples of their products). However, the fact that they are not consistently observed in the study examples or in other type III jackets nor have they been discussed by other researchers strongly indicates they were not “standard” for this type of jacket but represent a curious “anomaly” which cannot be explained.

Typical “Angular” RD type III collar examples (note similarity in form to Ramsey jacket):

George W Wilson Jacket (darts in neck)

Charles S Tinges Jacket

William S Pilcher Jacket (darts in neck)

Lewis K Knight Jacket

Lewis K Knight Jacket – Neck/Collar Close-up showing stitching

One characteristic observed on all the type II jackets in the study was the presence of a line of top stitching on the collar located above the seam between the collar and the neck. Other researchers have noted that this could be almost diagnostic of RD type IIs vs. type IIIs. In this study, such topstitching is noted on some RD type IIIs but is not universally found on all examples. In the close-up of the Knight jacket collar in this slide, the line of top stitching is clearly visible. It is also present on the Henry Redwood example seen from the inside of the collar (the post war red collar trim obscures it from the outside). None of the other RD type IIIs in the study group have this feature. The significance of this diversity is unclear. It could simply be a “seamstress choice” variation or it could be a change in assembly instructions by the RCB or possibly both. However, RD type III jackets were clearly made both ways.

All RD type III examples in the study do not have the “Angular” style collar described above. The Barnes jacket and the Tolson jacket both have a “rounded” profile collar like the style observed on most type IIs only lower in height (1” – 1 ¼”). Both jackets are possibly also among the latest type IIIs in the group based upon the service histories of their owners, issued in November or December 1864. It cannot be said that this represents a pattern change, but such a dramatic difference in the pattern piece profile is not likely a “seamstress choice” whim. It is simply noted as an “anomaly” which needs to be validated through further study.

E F Barnes Jacket

Thomas H Tolson Jacket

RD II and III Jackets – Lining

Based upon the examples studied, the design, construction philosophy, and material used in the linings of both RD type II and type III jackets was very similar and provides a consistent characteristic for identifying them. The Fifth Maine Museum jacket lining seen in this slide illustrates the typical characteristics of RD jacket linings. The body pattern used was of six pieces. The lining pieces were made of heavy, plain weave, unbleached or undyed cotton with attached inside facings made from the same material as the exterior of the jacket. The only exception to this is the Tolson jacket which has had the original lining replaced. A single interior pocket (nominally on the left side) was standard. On most examples this pocket was an inset or “slash” pocket set in the side panel of the lining. The construction/assembly philosophy on all the examples is consistent although some variation in the actual implementation is noted, especially in the way that the facings were attached to the lining side pieces and in the technique for closing the opening between the lining and inside collar. Other variations noted either appear to be mistakes or “goofs” by the assembler or field modifications to add a second inside pocket.

Four additional examples (two type IIs and two type IIIs) are shown in this slide. They indicate the consistency in design and material found among the examples studied as well as some of the “anomalies” encountered. Note that the Greer example has the single pocket but located on the right side and the Redwood example has its button holes placed on the right (wrong) side. Both are the only cases of such occurrences found in the jackets compared in the study and could represent possible mistakes by the pieceworker in assembly that were accepted by the RCB inspectors. In the Wilson example a second inside pocket was added after it was issued, perhaps as a field modification.

Typical lining configurations in other examples (RD II & RD III):

John J Haines Jacket (as manufactured)

George W Wilson jacket (right pocket added later)

George H T Greer Jacket (pocket on right side - possible “goof”)

Henry Redwood Jacket (buttons on left side – possible “goof”)

The story of the Thomas Hill Tolson jacket is an interesting example of how officers modified enlisted men’s clothing personalize it for their own use. Tolson apparently procured this jacket and a set of trousers (also made by the RCB) late in the war either at the time he was released from the hospital after five months recovering from wounds received at Cold Harbor or when a large issue of clothing was distributed to the company he commanded in the Petersburg trenches following his return to duty. Either way he elected to have modifications made to the garments to personalize them before he started wearing them. The quotation was made in Tolson’s diary on 10 February 1865 and indicates that he had the work performed by a tailor or seamstress in Petersburg for $100, which would have been equivalent to more than a month of his salary. The replacement lining was constructed of what appear to be scraps of two different wool or “wool on cotton” materials (inserts on the slide) and did not replicate the six-piece pattern of the original jacket. The original sleeve linings were retained, however. The modifications made to his “pants” were similarly oriented to personalizing them to meet his desires.

Thomas Hill Tolson Jacket – Original Lining Replaced: “Pay $100 to have my jacket and pants fixed in Petersburg. The weather wet and very cold” -Tolson’s diary, 10 Feb 1865

RD II and III Jackets – Breast Pocket

The inside pocket on the Fifth Maine Museum example is typical of the “slash” style inside pocket found in nearly all the examples in the study (if somewhat better executed than most). Only one inside pocket was provided “as issued” which, consistent with period practice, was normally found in the left breast area. They were inset into the side lining panel with the pocket bag turned inside through the opening. The ends were usually closed with button hole stitching. Often, a second inside pocket was added post manufacture on the right breast, in some cases inset like on the left, in others as a “patch” style applied over the lining.

The four pockets pictured also represent the typically encountered “as issued” interior pockets found in the study jackets both for type II and type III examples. Note both “whited brown” and vegetable/logwood dyed thread types were used. The stitching of the linings, construction of the pockets and closing the sleeve linings at the armscye was inconsistent either done with “whited” or vegetable/logwood dyed thread or a mix of both. Thread was likely included in the “kits” provided to the pieceworkers. The different colors could represent either that the RCB included whatever was available in the “kits” or that, since sewing thread was quite “dear” in the civilian market place, piece workers were substituting less valuable “whited” thread for the dyed version to keep that for their own use or to sell. Richmond newspapers at the time document the presence of “black market” trade in RCB goods including sewing thread.

John J Haines jacket

George W Wilson jacket

John Blair Royal jacket

George Pettigrew Bryan jacket

The one variant “as issued” inside pocket found among the study examples is shown in this slide. It is from the George William Ramsey jacket, which has already been noted for other unusual features. This jacket has a “patch” style pocket applied over the left breast lining, sewed in very neatly executed “running” stitches in the same thread as used in the rest of jacket. It is made from heavy cotton “osnaburg” identical in weave and coloration to the lining. The reason for this “anomaly” is unknown. It could represent a RBC experiment to simplify construction or merely a “seamstress choice” variation? A second “patch” pocket was also added after the jacket was made on the right side using a different cotton material.

George William Ramsey Jacket – “as issued” patch style Inner pocket RCB experiment to “simplify” construction or just “seamstress choice” ?

RD II and III Jackets – Sleeve Lining Attachment

In the typical construction of a RD jacket the body and body lining were assembled together and the collar closed at the neck before the sleeves are attached. The assembled sleeves were sewn in at the armscye with their linings left loose at the body end. The body lining was apparently sometimes basted to the body around the armscye to keep it in position during assembly. Once the sleeves were on, the sleeve linings were turned under and overcast onto the body lining. In the finished product the sleeve linings themselves are not sewn to the outer body but only to the body lining allowing for some relative movement of the lining when the jacket was being worn.

The pictures here show four additional examples illustrating the sleeve to body lining attachment construction methodology described above.

John J. Haines jacket

Joseph Woods Brunson jacket

George H. T. Greer jacket

George W. Wilson jacket

During construction, a convenient method for securing the body lining to the body shell prior to attachment of the sleeve linings is basting it at the armscye. The basting stitches were supposed to be removed after the sleeve linings are overcast down to the body lining. This technique is illustrated in this example (George Pettigrew Bryan jacket) where the worker assembling the jacket obviously forgot the last step!

Sleeve linings were attached at the sleeve’s cuff in several ways. In all cases both the sleeve and its lining were assembled together before attachment to the body. On some, the sleeve lining was first placed over the sleeve (wrong side out) and the two joined at the cuff end with a running stitch. Then the sleeve lining was turned inside and pulled through leaving a portion of the sleeve exposed inside below the seam with the lining (Haines jacket). On others the sleeve ends were first turned inside, and a seam allowance turned up on the lining at the cuff. The lining was then inserted inside the sleeve and secured to the sleeve with overcast stitching (Bryan and Knight jackets). Finally, on just one (the Greer jacket), the sleeve lining was inserted in the sleeve, the sleeve end turned up over the lining’s raw edge, and the two were fastened together by running stitches securing the turned-up edge of the outer sleeve to the lining in the arm above the cuff. This last technique was quite unusual based upon common period construction methods, perhaps showing inexperience on the part of the pieceworker who assembled it. The four pictures in this slide show examples of these different techniques.

John J. Haines jacket (lining sewn to sleeve end and turned)

George H T Greer jacket (lining secured with running stitches inside the sleeve)

George Pettigrew Bryan jacket (overcast)

Lewis W. Knight jacket (overcast)

RD II and III Jackets – Cuffs

The finished cuff was typically topstitched in the study examples. This was basically to hold the cuff “crease” line since there was no separate inside facing in the jackets examined. The sleeve ends were turned up (inside) and the sleeve lining attached to them as seen in the last slide. The distance of the top stitching away from the edge was somewhat variable but usually was between ¼” and ½”. The high stitching line on the Tinges jacket is unusual. Like the other jackets in the study its sleeves have been turned up at the cuff (i.e. there is no separate facing). However, there is no other top stitching present at the cuff and the visible stitching is placed about where the sleeve lining itself was typically attached suggesting that this is associated with attaching the lining. Unfortunately, the pictures available on this jacket (one not personally examined) are unclear on this detail but such a variation is certainly within the realm of “seamstress choice” differences.

Fifth Maine jacket

George W Wilson jacket

Joseph W Brunson jacket

Charles S Tinges jacket (note high stitching line)

Rank Insignia

Several examples in the study illustrate how rank insignia was handled on RD jackets. As has been discussed, commissioned officers were theoretically precluded from obtaining and wearing enlisted men’s clothing until 1864. On 4 March 1864, General Order 28, issued pursuant to an Act of the Confederate Congress, changed this. It stated “That all commissioned officers of the armies of the Confederate States shall be allowed to purchase clothing, and cloth for clothing, from any quarter-master, at the price which it cost the Government, all expenses included: Provided, that no quartermaster shall be allowed to sell to any officer any clothing or cloth for clothing which would be proper to issue to privates, until all privates entitled to receive the same shall have been first supplied.” This officially codified a practice which is believed to have been relatively common by officers in the field throughout the conflict. Three of the examples in the study were modified for use of line grade officers. The pictures below show the ways officer’s rank insignia was implemented on those jackets.

Non-commissioned officer insignia on enlisted RD jackets is seen in period photographs. The First Sergeant insignia on the Gettysburg NPS jacket is the only known (to the author) war era example of such insignia on one of them. The chevrons on the Henry Redwood example were clearly post-war additions. Researcher Dan Wambaugh indicates that they were applied after the jacket was issued. The chevrons on the jacket are neatly made, it appears, from medium blue “kersey” woven fabric and hand stitched directly to the sleeve without an underlay. The quality of the work suggests that they were done by a reasonably skilled worker. Certainly, it is possible that they were done by the Sergeant himself, but they also could be the effort of a local “seamstress” or perhaps a “Company tailor,” in the soldier’s regiment. Enlisted men charged with such field modification are noted in Union Army references and memoirs but are rare in those for Confederate forces.

Chevrons on Gettysburg NPS jacket

First Lieutenant Bars on Bryan jacket

Second Lieutenant Bars on Tolson jacket

Second Lieutenant’s Sleeve Braid and Collar Bars on Haines jacket

Second Lieutenant’s Sleeve Braid and Collar Bars on Haines jacket

Common Myths about Richmond Depot Jackets

Myth: English “Army Cloth” (EAC) was only used in late war examples, mostly RD type IIIs.

No: Examples exist as early the 2nd half of 1862 as well as throughout 1863. 14 of the 15 examples studied are EAC - 7 of the 8 type IIs & all of the type IIIs.

Myth: All EAC was the same.

No: English fabrics of different weaves, weights, and coloration were used by the RCB

Myth: All RD jackets were entirely hand sewn.

No: Machine sewing was sometimes used in the ‘63-’64 timeframe

Partial Myth: Construction differences were because of “seamstress choice” in assembly methods.

Yes, but…Different fabric types required/allowed different assembly methods

Some were probably “enabled” by differences in the “kits” supplied by the RCB

Some were simply “goofs” accepted by the inspectors

Based upon this very limited sample of the hundreds of thousands of uniform jackets made by the RCB during the war, several common perceptions or “myths” about “Richmond Depot” jackets can be clarified. First, the use of English “Army Cloth” or EAC has been characterized as only in late war products or that only RD type III jackets were made from such fabric. Of the fifteen examples considered in this study, fourteen are made from “Army cloth” imported from England and seven of these are RD type IIs. Many of these, including what is believed to be the earliest known “Richmond Depot” example, are from the first half of the conflict clearly suggesting that it was used through much of the war.

Furthermore, some authors have implied that all EAC was the same in weight, weave, or coloration. Major J. B. Ferguson, the Quartermaster’s purchasing agent in England, dealt with as many as 16 different mills and faced significant competition for what supplies were available. Apparently, while he did attempt to enforce quality standards, some material rejected by him was shipped by his suppliers to Nassau for transshipment on the Government’s account (Source: Wilson, Harold, Confederate Industry – Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War). Also as Nassau and Bermuda were home ports for the Blockade runners, goods they procured for the civilian market (including bulk woolen cloth) were purchased by agents posted in those locations by Quartermaster General Alexander Lawton for government use. It is very likely, therefore, that the “blue-gray English Army Cloth” that eventually reached Richmond for uniform production came from numerous sources and was of varying quality. This is directly demonstrated in the English woolen fabric used in the examples studied.

It has also long been the contention of many researchers that the jackets and other garments made by the RCB were always sewn by hand. This assumption certainly is supported by the production model adopted by the RCB in analogy with the Federal Schuylkill Arsenal. While most of the examples in this study are, in fact, constructed using hand stitching, two were largely or almost completely assembled using sewing machines. While certain elements were always done by hand (e.g. button holes and closing the lining seams between the body lining and sleeve linings at the armscye) both the Pettigrew and Brunson jackets have extensive machine stitching. In fact, other jackets in the extended group of RCB jackets also show varying degrees of machine stitching as well (see Part 3, “Stitching (by hand and by machine) and Thread” for an expanded discussion of machine sewing in RD jackets).

Finally. while all jackets in the study display some level of variance or “anomaly” in their pattern or construction, some of these were not simply “seamstress choice” differences. A few were probably the result of differences in the materials used and others were enabled by what was provided in the “kits” issued by the RCB. Several seem to be simply mistakes (“goofs”) made during assembly and passed by the Bureau inspectors (see Part 3, “Variations in Construction” for an expanded discussion of construction “anomalies”).

Together these factors begin to provide a view of how the RCB operated as evidenced in the products that were produced.

Characteristics in Summary

The “Jensen Characteristics” are valid across all 15 examples with a few minor additions

The number of front buttons is somewhat inconsistent (2 of 15 examples have fewer that 9 as do 3 others among the group of 10 other probable RD jackets)

RD type II jackets have a line of top stitching on collar above neck seam while type III’s were made either with or without one

Collar shape and height may relate to RD type – type II higher & rounded, type III “angular” (early?) or rounded but lower. (late?)

The transition between the type II and III jackets occurred after June 1864 and probably in the July/August 1864 timeframe

The Ramsey jacket could represent an example of a transition RD type II

Factory initiated RD type III pattern changes were made to “simplify” jackets and reduce assembly time

Neck darts are also seen in some type III examples

Several common “Myths” have been shown to be inaccurate based upon these 15 examples

The characteristics of uniform jackets produced by the RCB first described by Jensen largely were verified in the fifteen examples compared in this study (as they have been by all researchers in the years since 1989). Several relatively small additions or extensions do seem worthy of note. Jensen did point out that examples such as the Greer jacket (which he included in his article) were known that had fewer buttons than the nine normally found. Of the fifteen studied, two including the Greer jacket have less than nine as do three more in the extended group. Not challenging the “standard” presumption of nine, the number that have fewer can certainly be considered more than just random occurrences, however, given the observed rate. The line of top stitching found above the neck seam also is worth noting. While a characteristic on all RD type II examples studied, this feature was only sporadically seen in the type IIIs. Also, it seems, based upon the specimens considered, that type II jackets (save the Ramsey jacket) have a higher, more rounded profile style collar, some type IIIs (and the Ramsey jacket) have a collar with an “angular” profile, and some RD IIIs have lower rounded collars.

Information in original owner service records for some jackets and grouping of similar examples provides some relative estimate for when the type II to type III transition occurred. It seems that this occurred after June of 1864 and probably in July/August timeframe of that year. No type III examined could be logically assumed to have been issued before this period based upon its provenance and type IIs were still being issued at least as late as May of that year. Clearly several changes in the design of type IIIs identified by Jensen were seen in all such jackets in the study (i.e. elimination of epaulettes and belt loops). It was observed that the Ramsey jacket could represent a RD type II transition piece made that summer because of its collar style which is related to many type IIIs. Finally, the existence of two type III examples in the study (Wilson and Pilcher) with “darts” in the neck suggests other modifications in the pattern and construction may have been under consideration which were ultimately were not widely implemented.

As discussed in the last slide, examination of the examples in the study have also allowed some commonly believed myths surrounding Richmond jackets to be debunked.